One of the questions most frequently asked by new cosplayers is, "How do I start?" Whenever I get messages or comments with this question, I have to sit there and stare at the words for a while. Sometimes I'm not sure I understand what they're asking. I've been cosplaying for so long that all the prep work is almost second-nature, and my "start" of a project is buying the fabric and cutting into it, but that's not really the beginning.

First I choose what character I want to be, and then I study them. I stare at reference pictures, look up multiple angles and detail photos. I make sketches, even if they're not always good, to familiarize myself with details. I break down the costume into pieces and layers, and draw out each one. Then I look at material options, fabric types, what fabric folds and flows the way the character's does, what fabric the character would have access to, and what needs to be bought and where.

After you've got all of that down, and you know what you're getting yourself into, the fun starts. If I'm using fabric, I need a pattern that's at least close to what I'm making, and I'll probably need to make a mock-up to alter. If I'm making props, I study different techniques and materials to find the easiest and most cost-effective way to make the cleanest-looking prop possible. Probably do some test pieces first.

Then I just.. Do it! After collecting materials and resources, it's time to get things done! Pick a part, and start working on it!

How to Read Sewing Patterns (Part 3): Examples

Part 3: Examples

Examples

Simplicity

The following is a Simplicity pattern piece for a dress:

Each size that the piece comes in is written next to (usually inside of) the line that it corresponds to. The pattern also indicates its number (9), name (back lining), and what style of dress it's for (A).

Looking closer, the pattern also indicates to cut two pieces, in this case, they should be two mirrored pieces. An easy way to cut two mirrored pieces is to fold your fabric in half and pin it together. That way you only have to cut once, but you'll end up with two pieces. There are also notches to cut out in the arm hole, a straight of grain line and lengthen/shorten lines. On this dress, to shorten it, you fold on either of the lengthen/shorten lines and bring the fold up toward the dotted line.

Butterick

Here's an example of a Butterick skirt pattern:

This pattern shows the sizes (16, 18, 20) number (7), name (back), style (B), straight of grain line, and to cut 2.

The closer look at this pattern is more complicated. It uses diamonds and numbers to indicate pieces that need to be lined up. There are doted lines to indicate darts at the top. You would mark and sew on the dotted lines that correspond to the size you're making. The center back is marked, which just indicates where the middle of the back of the finished garment will be. Above that, there's a strange line with triangles on either size. This represents a zipper. This is an uncommon symbol, but was described in the instruction booklet, and is a good example of why it's always good to give the instructions a quick glance.

McCall's

Our next example was taken from a McCall's pants pattern, but was shortened because the bottom of the pattern had no symbols worth taking a look at (so pretend it's shorts):

Once again, we see the sizes, number, name, style, cut 2, and straight of grain.

This pattern uses diamonds and numbers to indicate which pieces line up. For example, you would look for another pattern piece that had two diamonds with a 6 next to them, and after you cut it out, that piece would be sewn to the top of this one so that the diamonds would match up.

Burda

This is one of the most complicated patterns I've ever used, so I thought it would be a good idea to include it here. It's a Burda brand sweater pattern:

This pattern uses dotted lines as the cutting lines to differentiate between sizes and patterns. Before we get into that though, let's look at the usual: it indicates size, number, name, style, and to cut 2. Now onto the slightly more confusing part:

The multiple dotted lines across the middle and bottom indicate which lines to cut on for different styles of sweater. The bottom lines are for sweater styles B and E, above that is for styles A and D, and finally the topmost ones are for style C.

Once you've figured out where to cut, it gets a little simpler, but still weirder than other patterns I've worked with. You can see three sets of lengthen/shorten lines. In addition, this pattern uses both circles and lines to show where to line pieces up. There are circles in the corners, with the numbers 1 and 2, so you would find other pieces with circles labeled 1 and 2 to line up there. Also on the left, there are short lines, one of which is labeled with a 3. To line this piece up, you'd look for another pattern piece that had the same lines and a 3.

Summary/Closing Thoughts

That's about all I can think to write about patterns. Hopefully this, in combination with Parts 1 and 2, will help a few people understand sewing patterns a bit more! As mentioned in Part 1, this tutorial was based on a panel that I gave at Fanime 2014. I'd love to give the panel again, as well as keep this guide as complete and up-to-date as possible, so please feel free to ask any questions you have and give me feedback!

How to Read Sewing Patterns (Part 2): Pattern Pieces & Vocabulary

Part 2: Pattern Pieces & Vocabulary

Pattern Pieces

Almost every pattern gives you pieces to make multiple things. The pattern used in this example can be used to make three different styles of a summer dress. This means that you're not going to use every single pattern piece enclosed.

Almost every pattern gives you pieces to make multiple things. The pattern used in this example can be used to make three different styles of a summer dress. This means that you're not going to use every single pattern piece enclosed.Some pattern instruction manuals will have a page that shows you exactly which pieces you need for each design. It looks something like this:

In the above example, you need the front, side front, back, side back, and shoulder strap for all of the dresses, and you can tell this because there's no style letter specified next to them in the list. On the other hand, you only need the ruffle and the linings for dress style A, and that's shown by the letter "A" written next to each one on the list.

Here's another example of how it may be shown:

This pattern is for a wizard costume, and is a little more complicated, but it's also laid out a bit easier. The costume piece that you can make is in bold, and then the pattern pieces you need to make it are listed below. (The list on the right is a Spanish translation.)

Another way you can tell what pieces you need is by checking farther into the instructions, near where they start talking about how to lay out the pattern pieces to cut them out of your fabric.

(I apologize for the blurriness, but I'll explain.) It specifies which dress style you'll be making, and then directly underneath says, "USE PIECES 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6". It should be noted that this does not include the lining, and the lining pieces are farther down the page. (You can see where it says "LINING A" at the bottom of the photo.)

If all of that is too cluttered-looking, or if the instruction booklet isn't laid out either of those ways for some reason, you can usually tell which pieces you need by looking at the pieces themselves. The following is from a Burda sweater pattern:

At the top is the piece number, followed by what piece it is. The letters below describe what style of sweater it can be used for. This piece can be used for sweater styles A, B, C, D, and E (all of which would be found on the front of the pattern packaging). This pattern piece also instructs the user to cut two pieces of it (usually mirrored pieces, further instructions for that would be found in the instruction booklet that comes with the pattern). There is a note that seam allowance is included, and then the pattern number.

Vocabulary

Here are some common symbols and vocabulary used in/on patterns.

Grain Line - "Place on straight grain of fabric parallel to selvage"

(This is the most difficult of the vocabulary to understand, so forgive me if this section is a little long.) The grain line is a (usually vertical) line with an arrow at each end (shown left). The selvage or "selvage edge" as it's sometimes called is the side of the fabric, as opposed to being the top or the bottom. On a bolt of fabric or a cut of fabric, the selvage edges are sometimes treated so that they won't fray, and they'll look different from the rest of the fabric in some way.

The grain line or selvage can also be called the weave. The weave is the "up and down" of fabric, and the "left and right" is called the weft. An easy way to remember this, as taught to me by my costume construction teacher, is that the weft goes "weft and wight" (left and right), and the weave is the other way. It sounds silly, but it's easy to remember.

So how do you tell which way is which? The easiest way is to watch the fabric being woven, but the second-easiest is to see it on the bolt before you buy it. Here I have a beautifully rendered MS Paint version of a bolt of fabric with everything marked:

The grain line on the sewing pattern lines up with the weave or the selvage. On the pattern piece, it usually looks like this (this is pattern piece number 3 of the dress pattern that I referenced earlier):

______________________________________________

Place of Fold - "Place the arrows facing the fold of fabric"

The place on fold line is bent at the ends with two arrows pointing toward the edge of the pattern. To use the place on fold line, fold your fabric in half, and line up the edge of the pattern that the arrows are pointing to with the fold of the fabric. After you cut out the pattern, you will have one symmetrical piece of fabric. Place on fold lines are often seen on the fronts of dresses and shirts, and sometimes on the backs of jackets.

______________________________________________

Notches - "Cut out notches on curved edges"

Notches are represented with triangles, and you cut them out of your fabric. They're seen on curves such as armholes and waists. This is so that when you either hem or line your garment, the fabric won't bunch up on the curve.

______________________________________________

Dots & Diamonds - "Line up pattern layers/edges"

Circles, diamonds, and sometimes other shapes, such as triangles or squares, are used to line up the pieces of your pattern that are meant to be sewn together. Sometimes the shapes will have numbers next to them, and you would for example line Circle 4 up with Circle 4, and Circle 2 lines up with Circle 2. Other times, there will be multiples of the same shape, so you would line up a row of three diamonds with another row of three diamonds, etc.

In the case of triangles, if they are pointing inward toward the middle of the pattern, they are notches and should be cut out, but if they are pointing outward and away from the pattern, they are used for lining up edges.

______________________________________________

Cutting Line - "Cut on this line to cut out your pattern"

Cutting lines can be solid or dotted, but are most often solid. If a pattern comes in multiple sizes, you can find the sizes written next to the cutting lines, and you would cut on the line that matches the size that you need.

______________________________________________

Lengthen or Shorten Lines -

- Make the garment longer by cutting between the lines and separating them the desired length.

- Make the garment shorter by folding on the lower line and bringing it closer the desired amount toward the top line.

Some patterns have more intricate instructions on lengthening or shortening garments, so always try to double-check.

______________________________________________

Dotted Lines - Usually the lines you sew on.

Examples:

- Seam allowances

- Darts

- Sometimes the cutting lines

Darts that show seam allowances are usually marked as "seam allowance", and darts are characterised by their triangular shape. If a dotted line is intended to be cut on, you will find the size number next to it, and it will sometimes have a pair of scissors printed on or near it.

[Part 1: Brands, Packaging, & Measurements | Part 3: Examples]

[Part 1: Brands, Packaging, & Measurements | Part 3: Examples]

How to Read Sewing Patterns (Part 1): Brands, Packaging, & Measurements

Since my "Sewing: How to Read Patterns" panel at Fanime went over so well, and because a couple of people requested it, I'll be basically converting the panel into written tutorials. (Maybe videos too, but don't count on it because I suck at doing videos.)

The brands that I used in this tutorial include:

In the top left-hand corner, there is a series of four numbers, this is the pattern number. The pattern number is not always at the top-left, sometimes it is centered or on the right, but it can usually be found at the top and will be a series of four numbers.

[Part 2: Patterns Pieces &; Vocabulary | Part 3: Examples]

Part 1: Brands, Packaging, & Measurements

Brands

There are a lot of different brands of sewing patterns, but in general, they use the same terminology and symbols.The brands that I used in this tutorial include:

- Simplicity

- Butterick

- McCall's

- Burda

Other brands include Vogue, New Look, Kwik-Sew, and many more. The overall simplest patterns to use are, as the name implies, Simplicity. Newer Simplicity patterns, dated from the 2000's onward, can still be quite complex, but not as much as some other brands. Older patterns, Simplicity or otherwise, such as those from the 1980's, are a lot simpler, but it's a bit of a double-edged sword. Though there's less terminology and symbols to look at, there's also less guidance. Older patterns were of the cut-and-sew variety, meaning the pattern was only there as a template, and most of the sewing that you had to do would be from memory or another guide source. Newer patterns give you guidance on sewing, but can be intimidating to look at.

Packaging

For this tutorial, I rely mainly on a slightly older Simplicity pattern. It's dated 1995 and is simple to look at, but also includes all of the terminology and symbols commonly seen across multiple pattern brands. The packaging contains only the pattern, not the fabric needed to make it. In a sense, it contains the stencil that you'll use to cut out your fabric.

Front:

Pattern NumberIn the top left-hand corner, there is a series of four numbers, this is the pattern number. The pattern number is not always at the top-left, sometimes it is centered or on the right, but it can usually be found at the top and will be a series of four numbers.

When you're buying patterns in a store, generally you don't dig through bins of patterns right away. There's usually a table and chairs with books of different patterns laid out. You look through the books, which show you pictures of the pattern packaging, and once you find one that you're interested in, you check the pattern number and then go dig through bins or drawers to find the actual package.

Pattern numbers are also useful to know when sharing information about patterns that you find useful. They're akin to a pattern's unique name, even though some newer patterns do have official names or titles, the most accurate way to describe a pattern is with it's number. This pattern would be described as "Simplicity 9682". Knowing the year also helps, because with new releases, pattern companies tend to re-use numbers. Generally it's not an issue though, because usually when we share pattern numbers, it's because the person we're sharing them with intends to go and buy it, and if it's still in stores, the pattern number is still the same.

Pattern Size & Measurements

Below the pattern number, or elsewhere on the top, depending on the brand, you can find the pattern size. Each pattern package contains three or four sizes.

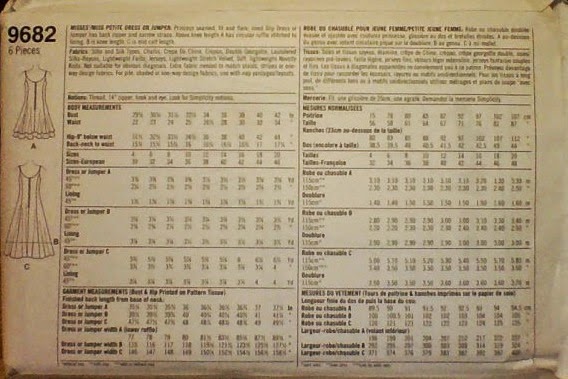

Pattern sizes vary dramatically from off-the-shelf clothing sizes. This one is labeled "Size U", which is about the most unhelpful size I've ever read. Next to that, it specifies "16, 18, 20", but these are not the same as a size 16, 18, or 20 dress that you would find in a store. On the back of the packaging, there is a list of measurements that indicate what size pattern you need. It usually looks something like this:

According to this pattern, someone with a 24 inch waist is a size 8. (Normally in off-the-rack clothing in the US, someone with a 24 inch waist is a size 0 or 2. In the UK, this is equivalent to a size 4 or 6.) If not all of your measurements match exactly to the same size, which they most likely won't because everyone's built differently, I recommend buying whichever size your largest measurement fits, because it's easier to alter patterns to be smaller than it is to make them larger. The only exceptions to this guideline include length measurements, such as back-neck to waist, since lengthening garments is relatively easy to do.

|

| Download it, save it, print it out, keep it. |

Knowing your measurements is a really important part of learning to sew for yourself, or if you're sewing for someone else, you need to know their measurements. Here's a really helpful chart for keeping track of your measurements. This chart also works for men, though men need an extra (inseam) measurement for pants as well. Do whatever you need to do to know these measurements as well as you can when you're shopping for patterns. You can memorize them, put them in your cell phone, write them on a post-it, or just plain bring the entire chart with you to the store. No one will care, I promise, we all just know that you're trying to get the best fit for your body, and that's admirable. The three most important measurements to know are bust, waist, and hips, unless you're only buying a pants pattern, in which case you'd need waist and waist to foot.

Back on the topic of the packaging:

Styles

Pattern "styles", or what the pattern will actually make, are indicated next to the picture(s) on the front of the pattern packaging.

Pattern "styles", or what the pattern will actually make, are indicated next to the picture(s) on the front of the pattern packaging.

This pattern can be used to make three different styles of a dress. The styles are labeled A, B, and C, where A is a summer dress with a sheer overlay, and B and C are single-layer summer dresses (no overlay), with B being a shorter version of C. It's a little confusing, but that's why there's pictures instead of just descriptions.

Back:

The back of this package looks really daunting. There's a lot of text and numbers, and it looks pretty complicated. Not to worry though, the entire right half is in French. Most patterns will have one or two translations, both on the package and on the pattern pieces themselves, and they're usually in Spanish and/or French.

Pattern Number

Again, the pattern number is on the top-left. It also says how many individual pattern pieces are included in this pattern. When you take the pieces out, they're on large sheets of this paper, and you have to cut them out first to use them with your fabric. This pattern has six pieces, so you might take out three large sheets of paper, and each large sheet will have two pattern pieces on it.

Again, the pattern number is on the top-left. It also says how many individual pattern pieces are included in this pattern. When you take the pieces out, they're on large sheets of this paper, and you have to cut them out first to use them with your fabric. This pattern has six pieces, so you might take out three large sheets of paper, and each large sheet will have two pattern pieces on it.

Back Details

Also on the left side, this package shows the back details for all of the styles of dresses shown on the front. Patterns with more variations or more pieces, such as accessories, will show more detail pictures so that you know exactly what you're getting.

Description, Fabrics, & Notions

At the top (disregarding the French half), you can find a detailed description of the garment that this pattern can make, what fabrics are recommended, and what notions you'll need. This one looks like this:

Some Quick Vocabulary:

- pile - The extra thickness of fabric that can be found in fabric types such as fleece and velvet.

- nap - The direction that the pile lays in, easiest to see in velvet or furs (the "correct" direction of the fur/velvet)

- You need extra fabric for thing such as pile or nap, because ideally the pile and nap should be the same throughout your clothing. If you're using fur, for example, you wouldn't want the fur on the front of a coat to go downward, the fur on the back to go upward, and the fur on the sleeves to go sideways. It should all go in the same direction, downward.

- notions - also referred to as "hardware"; pieces that you use in clothing that you cannot usually make yourself, such as zippers, hooks and eyes, thread, and buttons.

- Patterns will often recommend buying the same brand of notions to match the pattern. This is not only to promote their own products, but also so that all of your notions match the measurements of the pattern. For example, some hooks and eyes are looser or slightly larger than others depending on brand, and some zippers can be slightly narrower. It is best, if you can, to match the brand of notion to the brand of pattern that you're using.

Measurements, Size, & Fabric

I already covered measurements and size, but it come into play again here. The back of the packaging will also tell you how many yards of fabric you need to buy. Once you know your measurements and size, simply follow the column downward to the style you want to use, and the width of the fabric you're buying.

Fabric Width:

When you buy fabric, it's rolled up on a bolt (basically a rectangular piece of cardboard), and can come in a width of 45 inches or 60 inches. To actually purchase the fabric, you need to have it cut by an employee, and it's usually measured by the yard. In this example, if you're making a size 10 dress in style A, and your fabric is 60" wide, you'll need to have 2 and a half yards cut.

For other styles, just follow the column farther down.

Garment Measurements

At the bottom of the package, you'll find the actual measurements of the finished garment, or at least what they're supposed to be if you make it 100% correctly.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)